We still revel in claiming firsts: First Black person to be president, senator, congressman. And this is not just a United States phenomenon. It occurs across Africa and the African Diaspora.

Following enslavement and European colonialism across the Americas in particular, Black populations are still in the mode of recovery; gaining the kind of political and economic power that would advance our communities and ourselves. Political movements often provide the groundswell that allows for transformation and a period of necessary advance in spite of past setbacks.

And so, we move forward again: This time with a Black woman leading the advance, being nominated to be the vice president on a Democratic ticket in 2020. In spite of this year’s upheavals (COVID-19, the killing of George Floyd, the taking down of statues, the Black Lives Matter movement and related protests and uprisings in the United States and around the world), 2020 will prove to be a historic year for Black empowerment. We can still call this year, a year of the realization; a Black Women’s 2020.

What is significant to mark about this particular Black Women’s 2020 experience — which positions Kamala Harris as now ready to live out its promise is that it was cultivated out of the HBCU experience. For Howard University to be able to claim to have produced the first Black woman nominated to be the vice president of the United States is part of that historical promise that our ancestors imagined. When Howard students sing James Weldon Johnson’s Lift Every Voice and Sing, it is accompanied with a clenched fist, signaling a determination to prevail against that difficult past. The promise of the HBCU experience was precisely that: One would get a solid education while grounded in Black cultural experience. And Howard, often called the capstone, delivered from Zora Neale Hurston to Ta-Nehisi Coates; Houston Baker and Stokely Carmichael to Ras Baraka,the mayor of Newark, NJ.

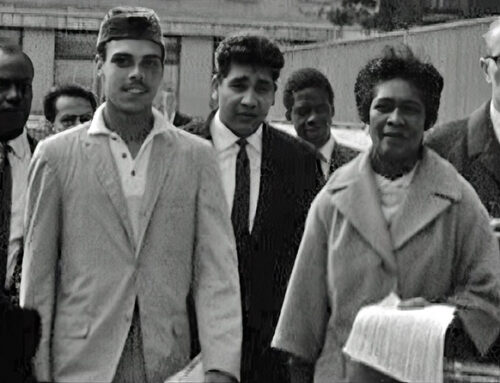

Howard is on the threshold of reclaiming its place in Black history if only for this latest reason, having educated the first Black vice president of the United States. For many years, before open access to Ivy League universities, following student activism of the 1960’s, Howard rivaled Harvard, similarity of names notwithstanding. It was the preference for African, Caribbean and African-American students to have a Howard University degree with a distinguished faculty who cared. Above all, it provided the confidence that one could indeed do and be anything.

Howard is on the threshold of reclaiming its place in Black history if only for this latest reason, having educated the first Black vice president of the United States. For many years, before open access to Ivy League universities, following student activism of the 1960’s, Howard rivaled Harvard, similarity of names notwithstanding. It was the preference for African, Caribbean and African-American students to have a Howard University degree with a distinguished faculty who cared. Above all, it provided the confidence that one could indeed do and be anything.

That confidence of being on a campus with Black men and women from all social and economic classes, national and ethnic origins also produced that variegated Black cultural experience. Automatically one is immersed in an international milieu where in Harris’s case of carrying both Afro-Caribbean and South Indian identities, made in the USA as a Black subject, would not have been an aberration. Additionally, Black sororities and fraternities on the campus were for many years a central feature in helping to develop a confident Black identity, holding one’s head high being one of its critical lessons. Both Alpha Kappa Alpha (1908) and Delta Sigma Theta (1913) were founded on Howard’s campus.

To pledge one of those founding chapters is to enter history and to connect with women who fought for Black women’s rights at the turn of the last century. And this is precisely what positions Harris as solidly within the U.S. Black community. But she also carries that global Black identity, and additionally her multiracial ethnic composition allows Jamaicans and Indians to claim her as do a range of other people of color. These links make a number of communities proud to identify and claim her as their own in a way that even exceeds Barack Obama’s ethnic identities.

Still, the United States, regardless of its international pre-eminence, has lagged behind the world in having women attain political leadership. Harris is the only Black woman who is a U.S. senator and the second in history after Carol Moseley Braun and once she becomes vice president there will be none. Those of us studying and observing this anomaly, like my university class on Black women and political leadership, wonder how the most advanced country in the world could still not have a woman in the highest rungs of political leadership.

It was only in the last 2018 election cycle that the U.S. moved to 23 percent leadership of women in the House of Representatives. A 2019 Pew Research report noted 12 percent Black representation in Congress. While there have been other Black women who have been nominated to the vice-presidential slot — Charlotta Bass (1874-1969) on the Progressive Party in 1952 and Rosa Clemente in the Green Party in 2008 — Harris becomes the first in a major party.

There is a cross-section of Black people who raise the same questions about some kind of essential Black identity and/or history that were raised when Barack Obama was nominated to lead the Democratic ticket in 2008. However, across the United States and around the world, women of a variety of political ideological positions, ethnic identifications and histories are running and being elected to political positions at the local, state and national levels. It is easy to assume that the days when Shirley Chisholm struggled to be taken seriously in a 1972 run for president are behind us. In fact, it is precisely the confidence to lead that Chisholm championed that makes a Harris vice presidency possible.

There is a cross-section of Black people who raise the same questions about some kind of essential Black identity and/or history that were raised when Barack Obama was nominated to lead the Democratic ticket in 2008. However, across the United States and around the world, women of a variety of political ideological positions, ethnic identifications and histories are running and being elected to political positions at the local, state and national levels. It is easy to assume that the days when Shirley Chisholm struggled to be taken seriously in a 1972 run for president are behind us. In fact, it is precisely the confidence to lead that Chisholm championed that makes a Harris vice presidency possible.

It is also significant that in the contemporary period, an activist group of young congresswomen known as The Squad (Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, Ayanna Pressley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) are not afraid to challenge open sexism and call it out publicly. For me, these provide the outer edges of self-articulation that allowed Harris to challenge the presidential nominee Joe Biden during the debate cycle, as she called out his particular anti-busing position, locating it squarely in American racism and herself on the other side of that history.

In the end, it was this boldness to challenge Biden that made Harris more recognizable as the strong candidate that she is and that those who know her prosecutorial history already recognized. These contrasting histories come together now to offer us the promise of her leadership. It is the boldness of the contemporary Black woman in 2020 that we are witnessing. This same audacity that propelled Harris to this position has been done throughout history, where Black women from Harriet Tubman to Shirley Chisholm were able to see ahead, with clear vision, and lead.

Carole Boyce Davies (Prof CBD)

Follow me on Twitter at @Ca_Rule